- Home

-

SHOP

- New

- Planners & Journals

- Art Prints

- Framed Prints

- Hand-Painted Domino Papers

- All Prints

- Notebooks

- Stitch-Bound Notebooks

- Wire-Bound Notebooks

- Journals & Planners

- Other Notebooks

- Leuchtturm1917

- Cards & Stationery

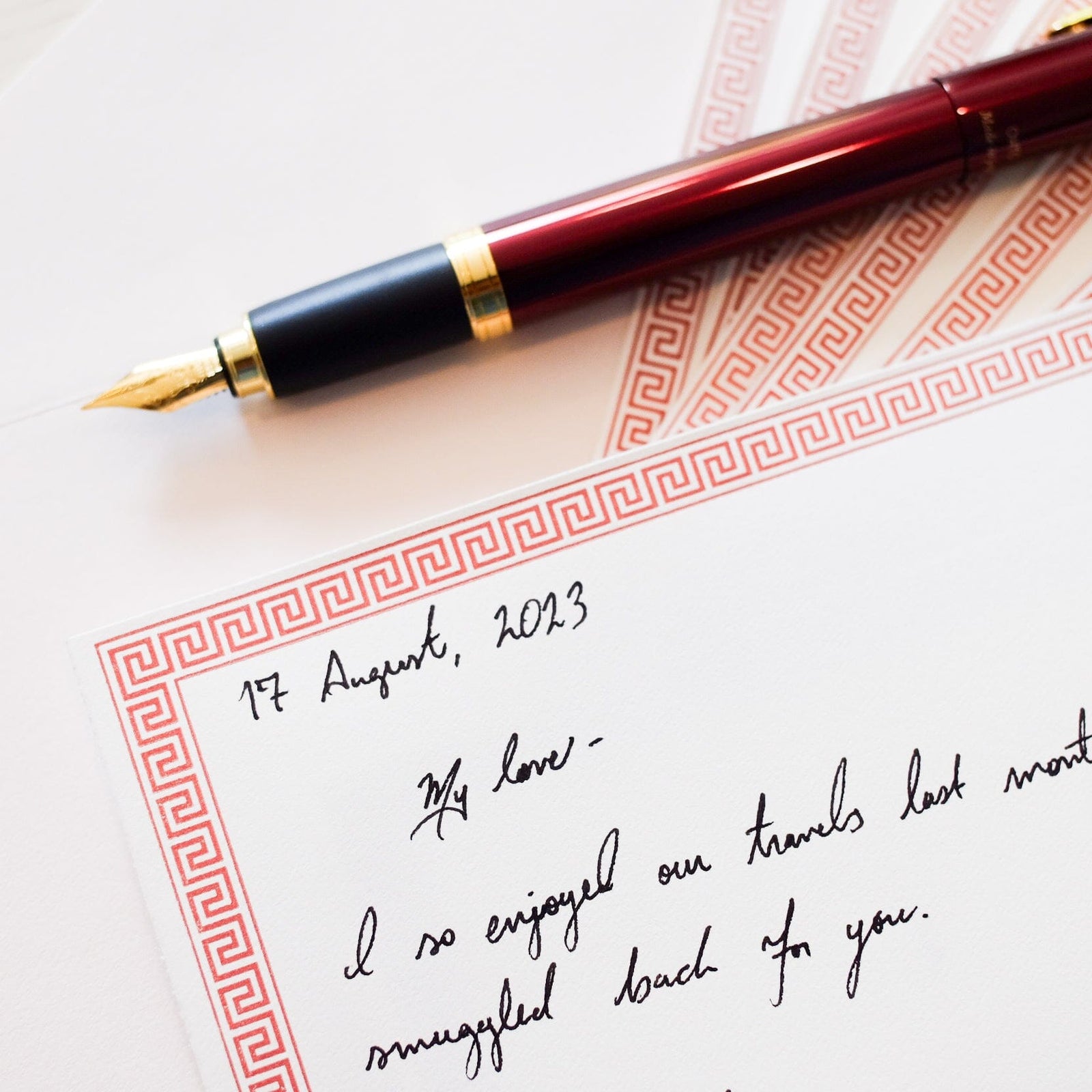

- Writing Stationery

- Greeting Cards

- Cambridge Imprint

- Writing Instruments

- Kaweco: Pens & Ink

- LAMY: Pens & Ink

- Ferris Wheel Press: Pens & Ink

- Pineider: Italian Fountain Pens

- Vintage & Antique Pens

- Midori & Pilot Pens

- Bottled Ink

- Calligraphy

- Vintage Pencils

- Blackwing

- Tombow

- Caran d'Ache

- Desk Accessories

- Paperweights

- Stickers

- Stationery Accessories

- Dresden Foils

- Clips & Letter Openers

- Erasers

- Table Linens & Home Goods

-

Events & Classes

- Contact & Locations

- Blog

-

Weddings

- Work With Us!

Jean McCormick

September 30, 2019

This was is very interesting and informative post on an historic paper design and its creator. I especially liked the detailed description of the making of the block and printing method. You seem to have produced a beautiful and faithful reproduction. Kudos and thanks.